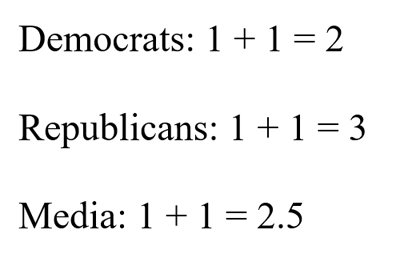

For some time, we have been examining why Republicans look at things so differently from Democrats. Much has been written about the Republican brain including a book by that title by journalist and author Chris Mooney. Mooney has been described as “one of the few journalists in the country who specializes in the now dangerous intersection of and politics.” His findings include evidence …. that among other things, many Republicans are not particularly concerned with evidence when it is not convenient to their arguments. Mooney also posits that Republicans are not as open to new information and experiences as others. They also seem to be lacking in empathy, as compared to others.

I recently adapted Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs of an individual to a comparable hierarchy of public citizen needs.

Being successful in caring about the first four levels (self, family, community, country & religion) is challenging enough for most people. Very few get to the fifth and highest level; caring about the “common good.” This may be in part because the demands of the previous four are so intense. But unlike many progressives, Republicans frequently have a sense of disdain towards the “common good.” This explains in part why they are so resistant to strengthening the safety net that the government has put in place to help care for those among us who are most in need.

What has been most frustrating and stifling to me is how journalists so willingly accept conservative ideas as equivalent to progressive ones. If the issue is what to do about gun violence in the United States, most in the media see two equally valid positions lined up against one another: protecting the Second Amendment and saving over 30,000 lives a year. If the issue is funding for school lunches, it’s the presumed equality of saving money by having kids go hungry vs. spending more money to keep children from starving.

It’s baffling to me how journalists can simply accept these false equivalencies. After all, most journalists are college-educated and took courses that required deductive reasoning and logic. It had been my impression, perhaps mistaken, that many students who went into the field of journalism did so because they wanted to uncover inequities and dysfunctions in our society. I thought that if they were to choose to not enter journalism, they might choose to go into fields such as sociology, psychology or international relations to try to be part of making a better world.

Fields like sociology, psychology and international relations focus on the dynamics of meeting the needs of individuals as well as serving the common good. Indeed, many individuals who enter those fields are able to look beyond their personal needs and consider what is best for all.

In fact, very few journalists seem to place much value in trying to be part of an effort to improve the common good. They may think that they are helping the world because they disclose information that can be beneficial to all of us. But disclosure without a sense of priorities is assembling a building without knowing which parts need to be put in place first. When the press reports on the total amount of campaign funds that a political candidate has raised, without providing information on who were the donors, and more importantly, what these donors might want in exchange, it is incomplete reporting.

It strikes me that there are two primary reasons why so few journalists factor the common good into their reporting.

- Media outlets are now strapped for cash. The industry has become much more competitive, and public loyalty to brands is much more fleeting than it used to be. So many media outlets, and this is particularly so in local news coverage, pander to a strange combination of “blood and guts” and civic boosterism.

- The field of journalism, like virtually all other professions, has a strong sense of clan. No matter how sleazy the output from a media source might be, the powers that be are always quick to point out that they are adhering to journalist ethics. This self-policing code references a number of factors, such as reliability of sources and providing accurate quotes. These are clearly important, but they do not necessarily touch on the “greater good” for the society in which they report. Loyalty to clan, or profession, is somewhat like “caring about one’s religion and country” in the public citizen hierarchy.

Item 4 could be something like:

Primary loyalty to profession is not unique to journalism. It’s certainly the case in education, the law, health care, and most other professions. But in journalism, parochial loyalty carries a special downside. Since journalists are reporting about “the world around us,” their purview should be broader than journalistic ethics. Ideally, they can give us the 30,000-foot, bird’s-eye view as well as the “up close and personal.” The means that with issues of state, they must be able to put happenings into context. When it comes to reporting many Republican talking points, this is where so many journalists seem to fail miserably.

Very few television journalists place the common good above all other concerns. Those who come to mind include Bill Moyers, Mark Shields and yes, David Brooks. Other than PBS, the perspective of other mainstream television journalists seems devoid of concern about the common good. Fox News obviously has a biased axe to grind. CNN uses hype as the path to higher ratings, so their concerns are primarily “what’s happening now” and what will bring us more viewers. MSNBC preaches a progressive agenda, but prefers to take cheap shots at conservatives rather than helping to explain the progressive perspective to those who may not be familiar with it. The process that they practice in presenting news rarely serves the common good.

As a society, we need more people to look at the broader issues that we face, rather than just what our professions teach us to be important. Professional practices, coupled with the pressures of raising revenue and cutting costs, make it difficult for journalists, attorneys, educators and others to place the common good as their first priority. Maybe what we need to do is the exact opposite of the current trend of training more people in the STEM fields. We need more philosophers who can help us sort this all out.