A great tradition of American business is to create demand when consumers are really not asking for anything. Nowhere is this more evident than in the way professional sports franchises work to expand their profits.

The National Hockey League is probably less guilty of excess than the National Football League, Major League Baseball or the National Basketball Association. But that did not keep the St. Louis Blues hockey franchise from taking the first step before going to the public well with an announcement on Oct. 1 that its home, the Scottrade Center “needs major renovation.” How major? Well, let’s say to the tune of $50 million. This comes at a time when St. Louis is succumbing to blackmail from the National Football League to build a $1 billion new stadium for the football Rams. Most opponents of this kind of bribery by a sports league or franchise say that the way to stop it is for a city to just say ‘no.’

As we have previously reported, this can be a very self-destructive approach for any single city to take toward a team or league. The corporations hold the best hand and can always take their chips and move elsewhere, most likely to a community that will do just about anything to gain the prestige of a new major sports franchise.

The St. Louis Blues are now saying that their building needs $50 million in renovations. The next step will be a not-so-veiled threat, asking (in the form of a demand) (a) for taxpayers to bear the cost of such renovations, or (b) for a new building to replace the 21-year old Scottrade Center, or (c) to leave St. Louis for perhaps Saskatoon (they did that once before), where they think they can get a better deal.

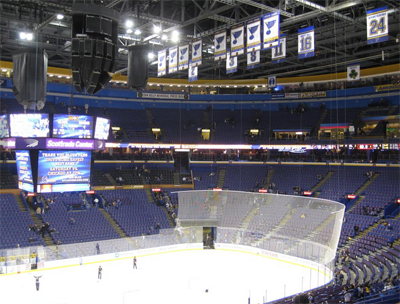

None of these options is good, and none of them is really necessary. Scottrade Center opened in 1994 at a cost of $200 million for construction. Much of this sum came from taxpayers. The typical cost of maintenance for such a building is two to three percent of the cost of construction per year. For Scottrade, that would be $4 to $6 million. As is the norm for professional sports franchises, the Blues, who own the building, do not make their books public. However, they are obviously doing maintenance on an on-going basis, and to most observers, the building seems very up-to-date.

I am reminded of the former St. Louis Cardinal baseball slugger, Mark McGwire. He is well known for his time in St. Louis as a prodigious home run hitter, for his use of a performance enhancing drug (PED) (which was legal in baseball at the time) and his failure to tell the truth before a Congressional committee investigating PEDs in baseball. Often forgotten is how he shilled for Cardinal owners in 2000, saying that Busch Stadium II (opened in 1966) was falling apart and that there was need for a new stadium. I maintain high respect for McGwire for a number of things, including walking away from $30 million in salary that he was due, because he felt that his knees would not permit him to be an effective player for the Cardinals. I don’t know what is worse, his trumpeting the Cardinals’ cause for a new stadium or the owners more or less putting him up to it. When in doubt, point the finger at the owners.

In any event, the Blues are now raising the “facility issue” only twenty-one years after the building opened. It’s not “state-of-the-art,” which is code for “help us find a way to get more public subsidies to cover expenses.”

Between 1960 and 2000, professional franchises in all sports built, or had built, new facilities. It made sense then because the older buildings were somewhat antiquated. The old Arena where the Blues initially played did not have air conditioning, and rest rooms could best be described as “a challenge.” But now we have franchises, particularly in football, asking for new stadiums when there is no demand for them from their fans. In fact, the fans resent the call for new facilities because ultimately they will pay for them as taxpayers.

We need to stop the madness. The first step is to allow the cities to “bargain collectively” with the owners and the league. It’s not just the players who need the protection of collective bargaining;  it’s the cities. Divided they fall, as one city after another succumbs to the demands of owners. The cities have little leverage. The only way to correct this is to form a committee at the U.S. Conference of Mayors of those cities with professional sports franchises. They need to (a) lobby Congress, the president and the courts to enact anti-trust legislation to stop the blackmail, and (b) for the cities to collaborate in refusing to give in. That leaves the leagues with no place to go.

it’s the cities. Divided they fall, as one city after another succumbs to the demands of owners. The cities have little leverage. The only way to correct this is to form a committee at the U.S. Conference of Mayors of those cities with professional sports franchises. They need to (a) lobby Congress, the president and the courts to enact anti-trust legislation to stop the blackmail, and (b) for the cities to collaborate in refusing to give in. That leaves the leagues with no place to go.

As is the case with so many problems in our country, we are distracted. Consumer focus is not an essential part of capitalism. The damage done by professional sports franchises to our communities is not our greatest problem, but the solution is one that is do-able and which does not involve public money. We need to shout a clear message that we know what they are up to and how to stop it. Can we do that without getting distracted? I’m not betting on it, but I’m hoping.